Imagine this scenario: You’ve started a new job and you’re building your team. Suddenly, you think of someone perfect for an open position—a talented former colleague who you know would be amazing in the role. But there’s a catch. You left your old company under less-than-ideal circumstances, and recruiting this person might look like you’re trying to poach their best talent.

Sound familiar? This situation happens more often than you might think, and it raises important questions about professional ethics, legal risks, and workplace relationships. Let’s explore everything you need to know about recruiting former colleagues without burning bridges or landing in legal trouble.

What Does “Poaching Employees” Actually Mean?

Employee poaching, also called talent poaching or employee raiding, happens when someone actively recruits employees from their former or competing companies. It’s different from someone independently applying to your organization—poaching involves reaching out to current employees and encouraging them to leave their jobs.

The term “poaching” carries negative implications, suggesting something sneaky or underhanded. However, recruiting talented people you’ve worked with before isn’t automatically unethical. The ethics and legality depend on how you go about it and what agreements you’ve signed.

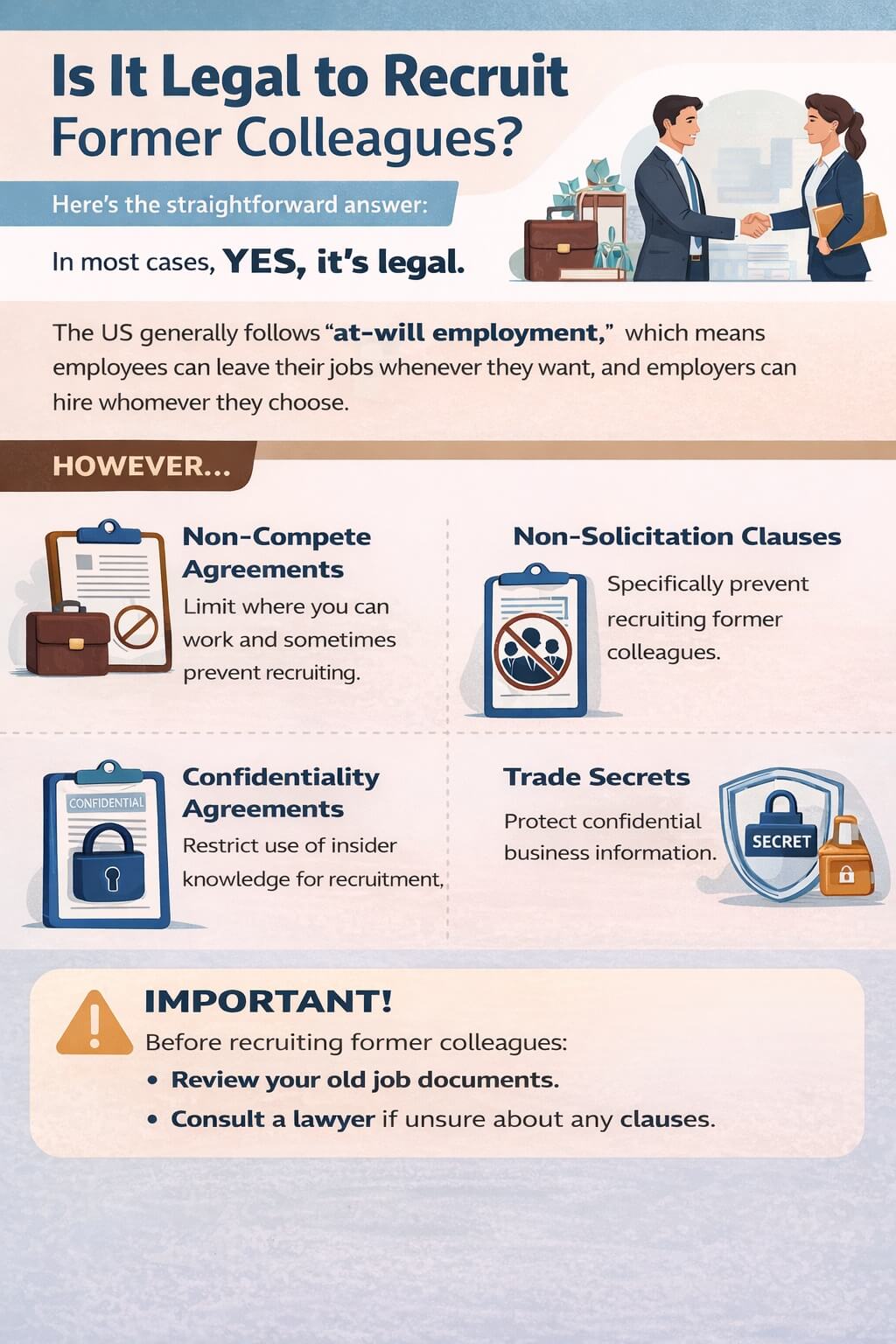

Is It Legal to Recruit Former Colleagues?

Here’s the straightforward answer: in most cases, yes, it’s legal. The United States generally follows “at-will employment,” meaning employees can leave their jobs whenever they want, and employers can hire whomever they choose.

However—and this is important—several factors can make recruiting former colleagues legally problematic:

Non-compete agreements restrict where you can work and sometimes limit your ability to recruit former colleagues for a specific period after leaving.

Non-solicitation clauses specifically prevent you from recruiting or “soliciting” employees from your former employer. These are more common than full non-competes and are often more enforceable.

Confidentiality agreements might prevent you from using insider knowledge about compensation, unhappiness, or specific skills to target recruitment efforts.

Trade secrets laws protect confidential business information. If you use proprietary knowledge to poach employees, you could face serious legal consequences.

Before you reach out to any former colleague, review every document you signed when you started and left your previous job. If you’re uncertain about any clause, consult with a lawyer or your current company’s legal department. It’s better to ask questions now than face a lawsuit later.

What Makes Employee Recruitment Unethical?

Even if something is technically legal, it might still be unethical. Here are situations where recruiting former colleagues crosses ethical lines:

Using confidential information: If you know someone is unhappy because you saw internal performance reviews or private communications, using that knowledge is unethical.

Targeting vulnerable employees: Reaching out to someone you know is struggling financially or emotionally, specifically to exploit their vulnerability, is questionable at best.

Mass recruitment campaigns: Systematically trying to recruit multiple employees to damage your former company goes beyond normal hiring.

Misrepresenting opportunities: Promising things you can’t deliver just to get someone to leave their current job is both unethical and potentially fraudulent.

Ignoring company policies: If your new employer has policies against recruiting from specific companies, violating these rules puts both you and the recruit at risk.

When Is It Okay to Recruit Former Colleagues?

Now for the good news: there are many situations where recruiting former colleagues is perfectly acceptable and even expected.

You left on good terms: If you had a positive departure and maintained professional relationships, reaching out about opportunities shows you value those connections.

Significant time has passed: The more time between your departure and your recruitment effort, the less problematic it appears. Six months to a year is often considered reasonable.

The person already expressed interest: If a former colleague previously mentioned wanting to work together again or asked you to keep them in mind, you’re responding to their interest rather than cold-calling.

You’re following proper channels: Going through official recruitment processes, letting HR handle outreach, and being transparent about your recommendation all demonstrate ethical behavior.

Your companies don’t directly compete: If your new company operates in a different industry or market, concerns about competitive harm are reduced.

The person’s skills are transferable: When you’re recruiting someone for genuinely different work that uses their general skills rather than company-specific knowledge, it’s less problematic.

The Guilt Factor: Should You Feel Bad About Recruiting Someone from a Difficult Situation?

Many managers feel guilty about recruiting former team members, especially when they know those employees are struggling in toxic work environments. This guilt often comes from feeling like you “abandoned” them when you left.

Let’s reframe this perspective: offering someone an opportunity to escape a miserable work situation isn’t betrayal—it’s potentially helping them. However, your motivation matters. Ask yourself:

Are you recruiting this person because they’re genuinely the best fit for the role, or because you feel guilty about leaving them behind? Guilt-driven decisions rarely work out well for anyone.

Can you actually offer them a better situation? If your new company has similar problems, you’re not helping—you’re just moving the problem.

Are you being honest about what you’re offering? Don’t oversell the opportunity just to make yourself feel better about recruiting them.

Remember: adults make their own career decisions. If you present an opportunity honestly and professionally, the other person can decide whether it’s right for them. You’re not “stealing” them—they’re choosing to explore new options.

How Might Your Former Employer React?

This is often the biggest concern when considering recruiting former colleagues. Your former employer’s reaction depends on several factors:

How you left: If you departed professionally with proper notice and maintained respectful relationships, they’re less likely to view recruitment as a personal attack.

The employee’s value: Recruiting an average performer might go unnoticed, but targeting their top talent will definitely get attention.

Company culture: Some organizations view employee movement as normal business, while others take it personally and may retaliate through legal action or reputation damage.

Industry norms: In some industries, movement between companies is expected and even celebrated. In others, it’s considered hostile behavior.

Your role in their development: If you hired and trained this person, some might argue you’re capitalizing on your former company’s investment in their development.

Possible reactions from your former employer include:

- Counteroffer attempts to retain the employee

- Negative references if future employers call them

- Legal action if they believe you violated agreements

- Informal industry reputation damage

- Accelerated vesting or retention bonuses to keep other employees

- Increased hostility toward you personally

Best Practices for Recruiting Former Colleagues

If you’ve decided to move forward with recruiting a former colleague, follow these guidelines to minimize risk and maintain your professional reputation:

Check your agreements first: Review all documents you signed with your former employer. If you’re unsure about any clauses, get legal advice before proceeding.

Get your current employer’s approval: Some companies have policies about recruiting from specific organizations. Make sure you’re not violating internal rules.

Be transparent: Don’t try to hide your connection to the candidate or your former employer. Honesty protects you if questions arise later.

Use proper channels: Let your HR department or recruitment team handle initial outreach when possible. This creates professional distance and documentation.

Keep it professional: Don’t badmouth your former employer or use negative information to persuade someone to leave. Focus on the positive opportunity you’re offering.

Document everything: Keep records of conversations, approvals, and processes you followed. This protects you if anyone questions your actions later.

Give them space to decide: Don’t pressure former colleagues into making quick decisions. Respect that they need time to consider their options.

Accept rejection gracefully: If someone isn’t interested, respect their decision and don’t make it awkward. They might be interested in the future.

Red Flags That Should Stop You from Recruiting

Sometimes the risks genuinely outweigh the benefits. Here are warning signs that you should probably look for other candidates:

You have an active non-solicit agreement: If you’re still within the timeframe of a non-solicitation clause, recruiting former colleagues could result in expensive legal battles.

Your departure was hostile: If there’s active animosity between you and your former employer, recruiting their employees will almost certainly escalate the conflict.

The person hasn’t shown interest: Cold-calling former colleagues who haven’t expressed any desire to change jobs can seem predatory.

You’re using confidential information: If your recruitment strategy relies on insider knowledge you shouldn’t have, stop immediately.

Your motivation is revenge: If you’re recruiting someone to hurt your former employer rather than because they’re the best candidate, your judgment is compromised.

The person is irreplaceable there: Recruiting someone whose departure would devastate projects or teams raises serious ethical questions.

Multiple people have warned you against it: If colleagues, friends, or your current employer’s HR team are all saying it’s a bad idea, listen to them.

What If the Former Colleague Reaches Out to You?

This scenario is much simpler and safer. If a former colleague contacts you asking about opportunities, you’re responding to their initiative rather than poaching. This dramatically reduces legal and ethical concerns.

When former colleagues reach out:

- Be honest about available positions and whether they’d be a good fit

- Still follow your company’s standard application process

- Disclose your previous working relationship to relevant parties

- Don’t promise anything you can’t deliver

- Let them make the decision without pressure

Even in this scenario, check your agreements to make sure you’re not prohibited from even discussing opportunities with former colleagues.

Alternatives to Direct Recruitment

If recruiting a former colleague seems too risky but you genuinely believe they’d be great for your team, consider these alternatives:

Post the job publicly: Share job postings on professional networks where former colleagues might see them without direct solicitation.

Have someone else reach out: If your company’s recruiter contacts them as part of normal sourcing, you’re less directly involved.

Wait for the right timing: If you’re still within a non-solicit period, simply wait until the restriction expires before making contact.

Provide references: If the person applies independently, you can support their application through the normal process.

Build long-term relationships: Stay in touch professionally without recruiting. When the timing is right naturally, opportunities may arise.

Making the Final Decision

Ultimately, deciding whether to recruit a former colleague requires balancing several factors: legal risks, ethical considerations, potential benefits, and long-term career implications.

Ask yourself these final questions:

Is this person truly the best candidate for the role, or are you letting familiarity cloud your judgment? Would you recruit them if they weren’t a former colleague?

Can you make this decision transparently and defend it if questioned? Would you be comfortable if your actions were made public?

Have you minimized legal and professional risks as much as possible? Have you consulted the right people and followed proper procedures?

Are you prepared for potential consequences from your former employer? Have you honestly assessed the worst-case scenario?

Is this worth potentially damaging your professional reputation? How might this decision affect future job prospects?

If you can answer these questions satisfactorily and you’ve followed proper legal and ethical guidelines, recruiting a talented former colleague can be a win for everyone involved. The key is approaching the situation with integrity, transparency, and respect for all parties—including your former employer, even if you didn’t part on the best terms.

Remember: in the interconnected professional world, your reputation follows you everywhere. Making ethical decisions about recruitment, even when it’s inconvenient, protects your career in the long run and helps build a professional brand based on integrity rather than short-term gains.