You’ve spent hours reviewing resumes, conducting multiple interview rounds, and carefully checking references. The candidate looks amazing on paper with the perfect education, impressive job titles, and all the right keywords. You make the hire feeling confident, only to discover within weeks that this person can’t handle basic workplace situations, crumbles under pressure, or creates drama with everyone on the team.

This frustrating pattern happens in companies everywhere. Hiring managers are getting really good at filtering resumes and spotting technical qualifications, but somehow missing the crucial traits that actually predict job success. You can teach someone a new software program or technical skill, but you can’t easily teach emotional maturity, resilience under stress, or the ability to work well with others. Yet most hiring processes barely scratch the surface of these make-or-break qualities.

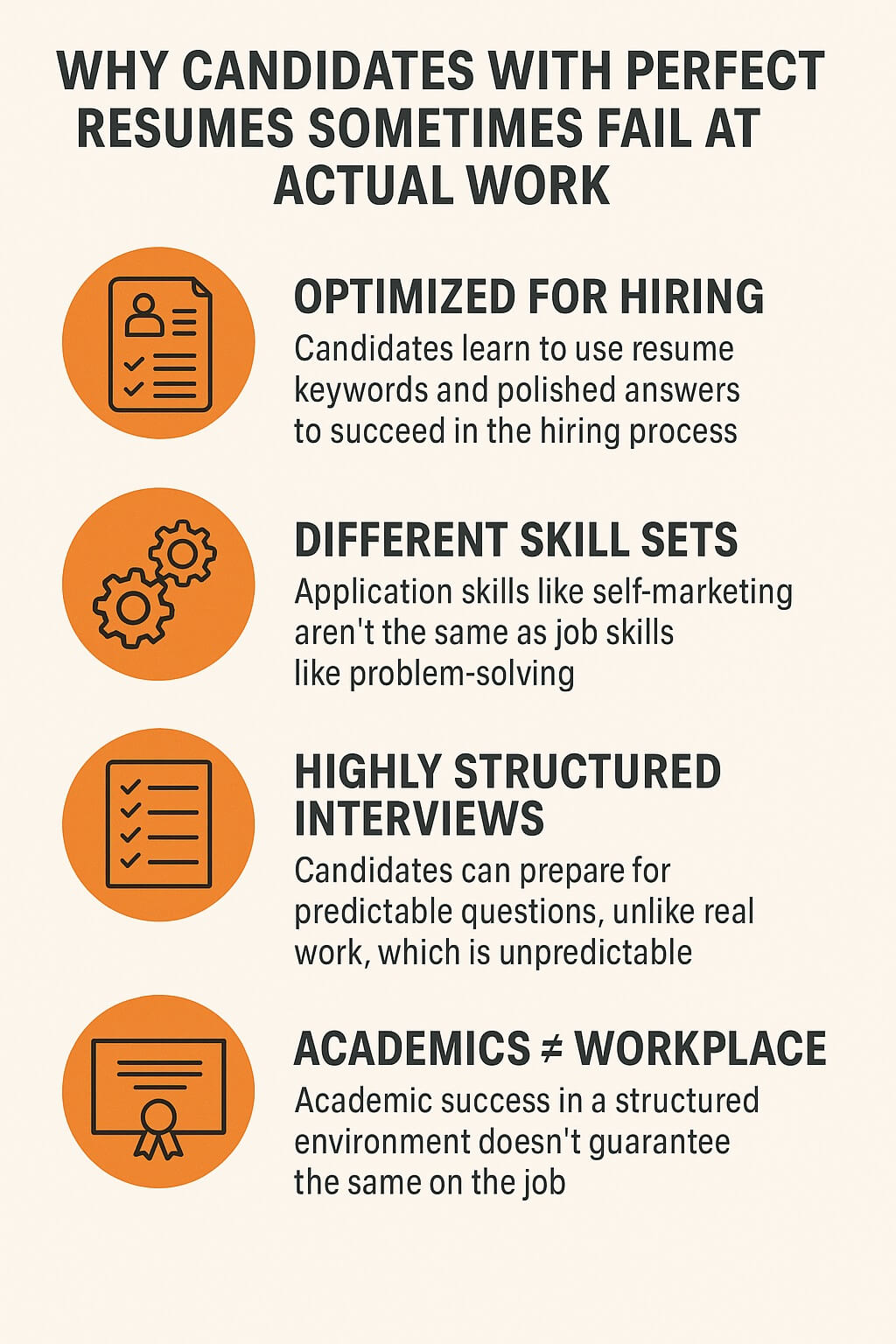

Why do candidates with perfect resumes sometimes fail at actual work?

The modern job application process has become a game that some people are really good at playing, even if they’re not good at the actual job. Candidates learn to optimize their resumes with specific keywords that will get past automated screening systems. They practice answering common interview questions until their responses sound polished and professional. They know how to present their experience in the best possible light, even if the reality was less impressive.

Being good at applying for jobs requires a completely different skill set than being good at doing jobs. Application skills involve marketing yourself, telling compelling stories about your achievements, staying calm during interviews, and knowing what recruiters want to hear. Job skills involve handling unexpected problems, working with difficult people, managing stress when deadlines pile up, and maintaining good performance even when things get messy. These two skill sets don’t necessarily overlap.

Some candidates are genuinely skilled at both, but others have invested heavily in perfecting their application game while their actual work abilities remain average or below. They might have taken resume writing courses, worked with career coaches, practiced mock interviews dozens of times, and studied exactly what to say in different interview scenarios. All that preparation makes them look incredible during the hiring process, but it doesn’t make them better at the job itself.

The interview environment is also highly structured and controlled, which helps candidates who struggle with the unpredictable nature of real work. Interview questions, even behavioral ones, are somewhat predictable. Candidates can prepare stories ahead of time and present themselves at their absolute best for a few hours. Real work involves constant surprises, unclear situations, and performance that needs to stay strong day after day, not just during a planned interview slot.

Academic success, which looks impressive on resumes, measures a specific type of intelligence and work ethic that doesn’t always translate to workplace success. Someone can earn perfect grades by excelling at structured assignments with clear requirements and predictable evaluation criteria. The workplace rarely works this way. Projects change mid-stream, expectations aren’t always clear, and success often depends more on how you handle ambiguity than how you perform on well-defined tasks.

How can I spot emotional intelligence during the hiring process?

Emotional intelligence doesn’t show up on resumes, and candidates rarely admit during interviews that they struggle with self-awareness or managing relationships. You need to look for it through indirect clues and specific questions that reveal how candidates actually handle interpersonal situations.

Pay close attention to how candidates talk about previous coworkers and managers. Someone with low emotional intelligence will often blame others for problems, describe conflicts where they were completely right and others were completely wrong, or speak dismissively about people they worked with. People with high emotional intelligence typically acknowledge their own role in difficult situations, show empathy for others’ perspectives even in disagreements, and can describe what they learned from challenging workplace relationships.

Ask candidates to describe a time when they received criticism or negative feedback. The specific content of the story matters less than how they tell it. Do they get defensive just describing the situation? Do they acknowledge any validity in the feedback, or do they explain why the other person was wrong? Can they describe how they responded productively, or does the story focus on how unfair the situation was?

Notice how candidates interact with everyone they encounter, not just the hiring manager. How do they treat the receptionist, administrative staff, or junior team members they meet? Someone with good emotional intelligence treats everyone with respect regardless of their position. Someone lacking it might turn on charm with decision-makers but show their true colors in how they treat people they think don’t matter.

Look for self-awareness in how candidates describe their weaknesses or areas for growth. Generic answers like “I’m a perfectionist” or “I work too hard” suggest someone who isn’t genuinely reflective about their limitations. Real self-awareness sounds more like “I sometimes jump to solutions too quickly without fully listening to my team’s input, so I’ve been working on asking more questions before sharing my ideas.”

Consider including someone from a different department or level in the interview process. People with low emotional intelligence sometimes struggle to adjust their communication style appropriately for different audiences. Can the candidate explain technical concepts clearly to a non-technical interviewer? Do they talk down to junior staff or show off their knowledge inappropriately?

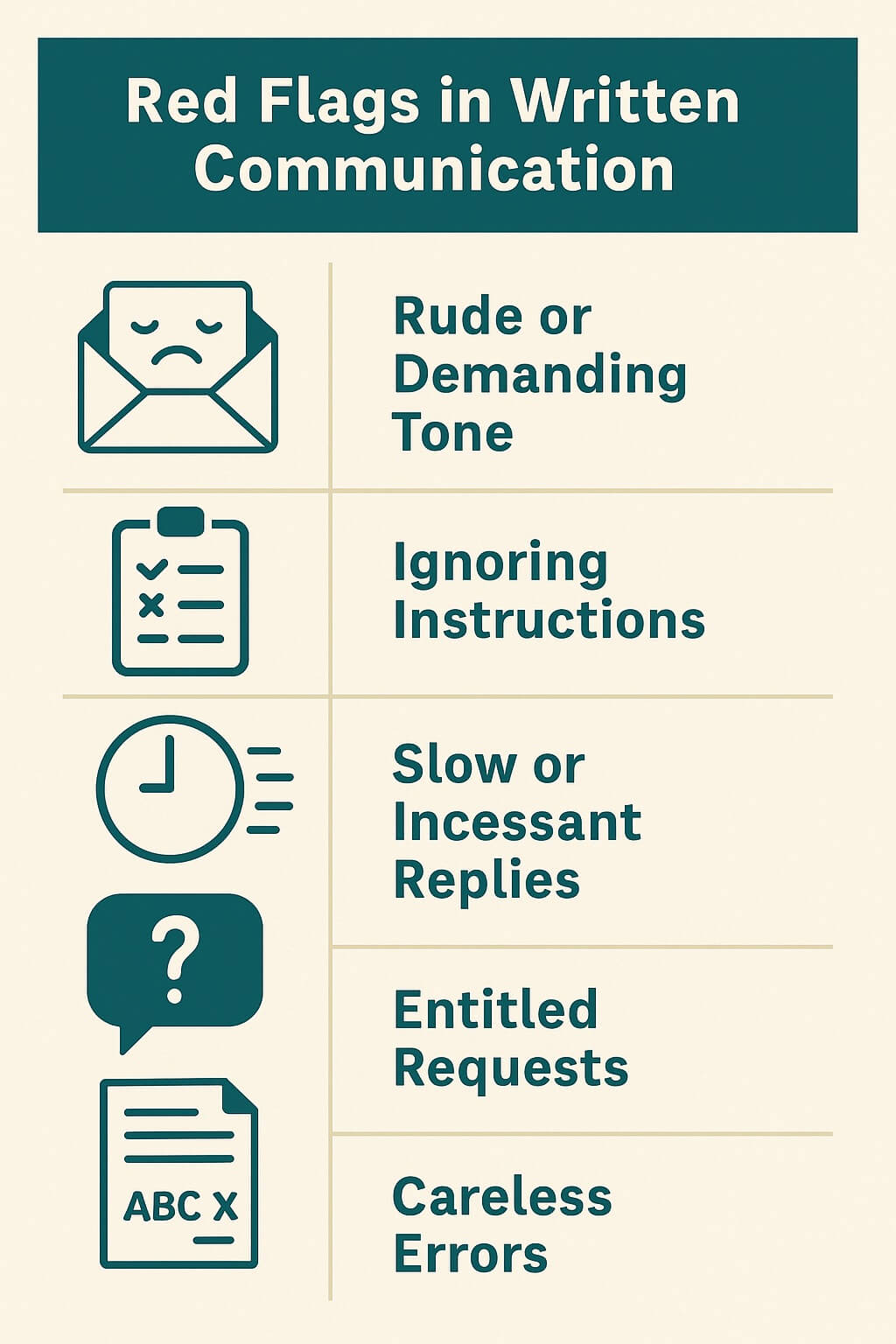

What are the red flags I should watch for in written communication?

Written communication during the hiring process often reveals personality traits that predict workplace problems, but many hiring managers dismiss these early warning signs because the candidate looks good otherwise. Taking communication red flags seriously can save you from bad hires.

Watch for tone issues in emails. Does the candidate come across as demanding, entitled, or oddly familiar before they’ve even met you? Do they make assumptions about your time or flexibility without any relationship basis? Someone who sends pushy or presumptuous emails during the application process will likely bring that same tone to workplace communications.

Notice how candidates respond to requests or instructions. If you ask them to complete a task as part of the application process, do they follow directions precisely, or do they ignore parts they don’t like? Someone who can’t follow simple application instructions probably won’t follow workplace procedures either. How they handle small requests during hiring predicts how they’ll handle assignments if hired.

Look at response times and communication patterns. While everyone has different schedules, someone who consistently takes days to respond to time-sensitive hiring communications might have similar habits with workplace deadlines. Similarly, someone who sends multiple follow-up messages within hours might struggle with patience and respecting others’ time.

Pay attention to how candidates ask questions or request information. Do they phrase requests professionally and respectfully? Or do they make demands without pleasantries? The way someone asks for information about salary, benefits, or schedule flexibility reveals their interpersonal approach. Professional curiosity looks different from entitled demanding.

Grammar and spelling matter, but not because perfection is required. What matters is whether the candidate puts in appropriate effort for the context. A few typos in a casual email exchange isn’t concerning, but a cover letter or formal application filled with errors suggests carelessness or lack of attention to detail. Someone who can’t proofread their job application probably won’t proofread their work either.

How do I test for performance under pressure without multiple interview rounds?

Multiple interview rounds are exhausting for both candidates and hiring teams, and they still often fail to reveal how someone handles stress. Building pressure tests into earlier stages of the process saves time and gives you better information.

Consider adding a short, practical assignment early in the hiring process that requires candidates to work under time constraints. This doesn’t need to be a full project that takes hours. A thirty-minute exercise that asks candidates to respond to a realistic workplace scenario shows you how they think and perform when they can’t rehearse perfect answers. You learn more from watching someone solve a problem in real-time than from hearing them describe how they solved problems in the past.

The specific content of the exercise matters less than the conditions. You want something slightly stressful with unclear parameters, similar to what they’d face in the actual job. Can they make reasonable decisions with incomplete information? Do they ask clarifying questions or make assumptions? How do they communicate their thought process? Do they fall apart when things aren’t perfectly clear?

Group interviews or exercises can reveal how candidates handle pressure while also showing interpersonal skills. Put multiple candidates together for a discussion or collaborative task, and you’ll see who dominates conversations, who contributes thoughtfully, who helps others, and who shuts down under the stress of performing with peers watching.

Phone or video screens earlier in the process should include at least one or two questions the candidate definitely hasn’t prepared for. Ask them to explain something technical to you as if you know nothing about the field, or present them with a hypothetical problem they need to think through on the spot. Perfect candidates should be able to think on their feet, not just recite prepared answers.

Simulations of actual work tasks provide the best prediction of job performance. If the job involves customer service, have candidates handle a mock difficult customer interaction. If it’s a creative role, give them a quick brainstorming challenge. If it involves data analysis, provide a small dataset and ask them to identify the most important insights in ten minutes. These exercises show you the person’s actual abilities, not their ability to talk about their abilities.

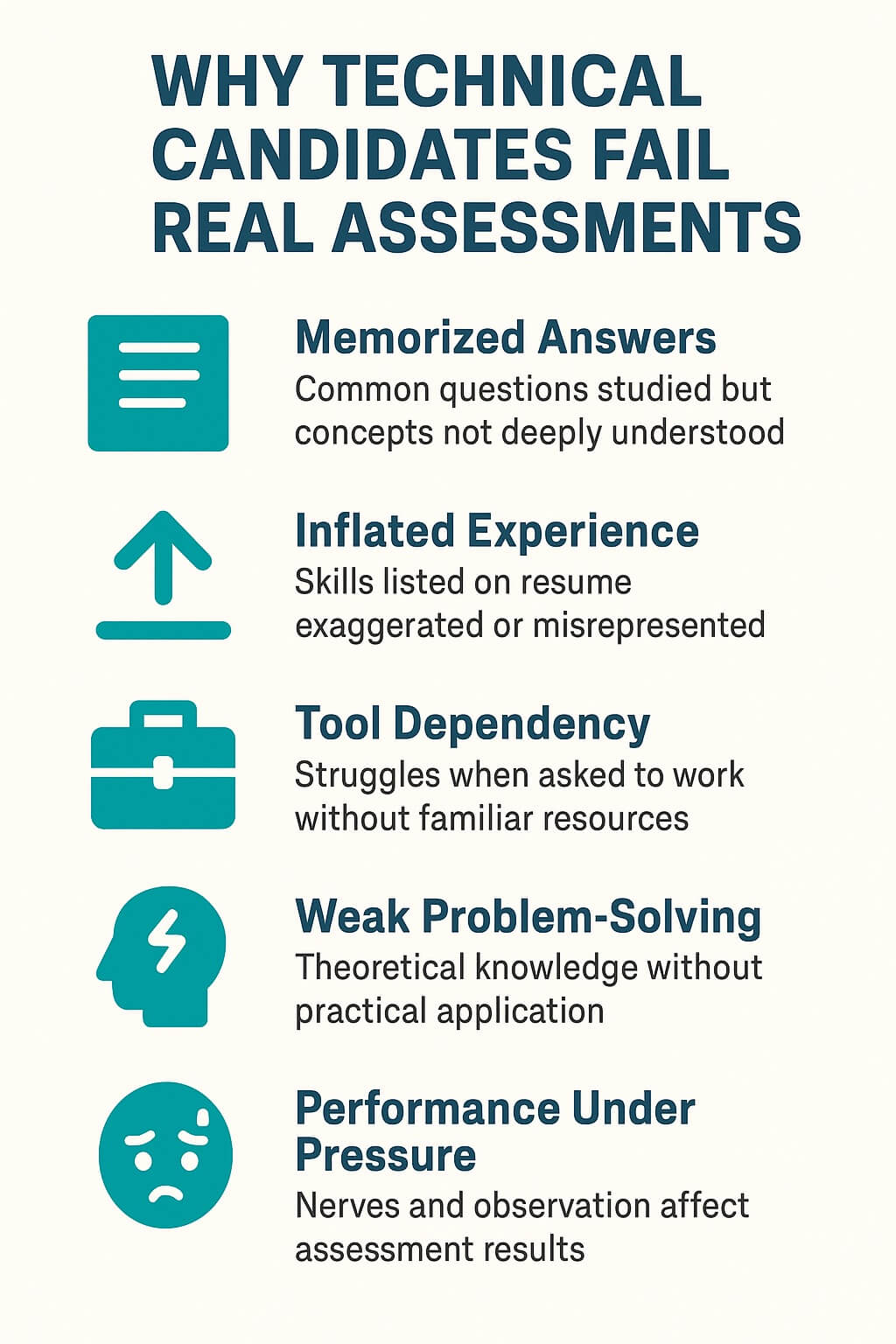

Why do technical candidates who pass pre-screens fail actual assessments?

The gap between passing pre-screen questions and performing well on deeper technical assessments often reveals that candidates memorized answers or inflated their experience rather than genuinely possessing the skills. Understanding this pattern helps you design better screening processes.

Many candidates study common pre-screen questions and learn acceptable answers without deeply understanding the concepts. They can define technical terms and describe processes they’ve read about, but they can’t apply that knowledge to solve actual problems. Surface knowledge is enough to sound competent during a short conversation but falls apart when tested with real scenarios.

Resume inflation is incredibly common in technical fields. A candidate might list a technology on their resume because they used it once during a training course or watched a team member work with it. When they say they have “experience” with something, they might mean they’ve heard of it and could probably figure it out if given time, not that they can actually use it proficiently right now.

Some candidates rely heavily on specific tools, templates, or resources they’ve used in previous roles. When asked to demonstrate skills in a different environment or without their usual supports, they struggle because their competence was more about knowing where to find answers in their old workplace than actual independent skill. They can operate fine in a familiar context but can’t transfer that knowledge to new situations.

Candidates sometimes pass initial screens because they’re good at theoretical knowledge but lack practical problem-solving skills. They can discuss best practices and recall textbook solutions, but when faced with messy, real-world problems that don’t match the textbook scenarios, they don’t know how to adapt their knowledge. Theory and practice require different types of thinking.

Pressure and observation also affect performance. Some people who can solve problems fine when working alone get nervous and perform worse when someone is watching and evaluating them. This is a real issue because some jobs do involve working under observation or presenting solutions to stakeholders. A technical assessment reveals not just skills but also confidence and composure under scrutiny.

What questions actually reveal how someone will perform at work?

Traditional interview questions often produce rehearsed answers that tell you little about real performance. Shifting to questions that require genuine thinking and self-reflection gives you much better information about who the candidate actually is.

Instead of asking about strengths and weaknesses, ask candidates to describe a project they’re proud of, then drill down into the specific details. What was their exact contribution versus what the team did? What went wrong that they had to fix? What would they do differently if they could redo it? Candidates who did the work can answer these questions easily and specifically. Those who exaggerated their role get vague or contradictory when you dig deeper.

Ask about specific interpersonal conflicts rather than general teamwork questions. “Tell me about a time you disagreed with a coworker about how to approach a problem. What was the disagreement about, how did you handle it, and what was the outcome?” This reveals emotional intelligence, conflict resolution skills, and whether they can maintain relationships while navigating disagreements.

Questions about failure reveal more than questions about success. “Tell me about a time you made a significant mistake at work. What happened, how did you realize the mistake, what did you do about it, and what did you learn?” People with good judgment and emotional maturity can discuss failures honestly and focus on learning. Those lacking these qualities either claim they’ve never made mistakes or blame circumstances and others.

Ask candidates to teach you something. “Explain a concept from your field to me as if I know nothing about it. Help me understand it well enough that I could explain it to someone else.” This tests communication skills, patience, ability to adjust to their audience, and depth of understanding. People who truly understand something can explain it simply. Those with surface knowledge hide behind jargon.

Hypothetical situational questions work better when they’re specific and realistic for your workplace. Instead of “How would you handle a difficult customer,” describe an actual difficult situation from your company and ask how they’d approach it. What would they do first? What information would they need? How would they decide between different options? Their thought process matters more than whether they choose the “right” answer.

How can I filter for people who won’t become toxic coworkers?

Toxic employees destroy team morale, drive good people to quit, and create far more damage than whatever work they produce. Screening for toxic traits during hiring is much easier than dealing with a toxic person once they’re on staff.

Look for patterns of playing the victim in past work situations. When candidates describe why they left previous jobs or explain conflicts, notice whether they take any responsibility or if everything bad that happened was someone else’s fault. People who externalize all blame tend to continue that pattern, creating drama and conflict in their new workplace.

Watch for signs of grandiosity or dismissiveness toward others. Does the candidate talk about being the only competent person on their previous team? Do they imply they’re smarter than their former managers? Do they roll their eyes or make subtle digs about others during interviews? This attitude doesn’t improve after hiring; it typically gets worse.

Notice how candidates respond when you challenge their statements or ask for clarification. Do they get defensive, argumentative, or condescending? Someone who can’t handle gentle questioning during an interview definitely can’t handle constructive feedback as an employee. Emotional reactions to neutral questions are serious red flags.

Ask about how they’ve helped others succeed or supported teammates. People who care about collective success tell stories about collaboration, mentoring, or going out of their way to help coworkers. Toxic individuals struggle to tell these stories because they genuinely don’t think much about others’ success. Their stories all center on their individual achievements.

Check references carefully and read between the lines. When former managers or coworkers give lukewarm references, praise only technical skills while avoiding comments about personality or teamwork, or provide the bare minimum information, they’re probably trying to politely signal problems without saying something that could be legally problematic. Enthusiastic references about someone being a joy to work with matter as much as praise for their technical abilities.

Should I rethink which skills I’m actually screening for?

Many hiring processes optimize for the wrong things because technical skills are easier to measure than the attributes that actually predict success. Rethinking your priorities can dramatically improve hiring outcomes.

The skills that show up on resumes and are easy to test are often not the skills that make the biggest difference in job performance. Yes, someone needs baseline technical competence for the role, but beyond that threshold, things like adaptability, communication, emotional intelligence, resilience, and judgment matter more. Two candidates with similar technical skills can have vastly different impacts based on these softer attributes.

Consider which challenges cause the most problems in your current team. Do projects fail because people lack technical knowledge, or because team members don’t communicate well? Do employees struggle because they don’t know the tools, or because they can’t handle changing priorities and ambiguous situations? Your hiring process should screen hardest for whatever issues create the biggest actual problems.

Willingness and ability to learn often matter more than current knowledge, especially in fields that evolve quickly. Someone who learns fast, asks good questions, and stays curious will outperform someone with slightly better current skills but fixed in their thinking. Questions about how candidates learn new things, what they’ve taught themselves recently, and how they stay current reveal learning orientation.

Cultural fit is real, though the term gets misused. You’re not looking for everyone to be the same or to hire only people you’d be friends with. You’re looking for people who align with your workplace’s actual values and can thrive in your environment. If your workplace values direct communication, someone who gets offended by straightforward feedback won’t be happy. If your culture is collaborative, lone wolves will struggle. Be honest about what your workplace is actually like and hire people who match that reality.

Problem-solving ability and judgment are harder to test than specific knowledge but more valuable. Can the candidate break down complex problems, think through tradeoffs, and make reasonable decisions with imperfect information? These capabilities transfer across specific tasks and technologies, while memorized knowledge becomes outdated.

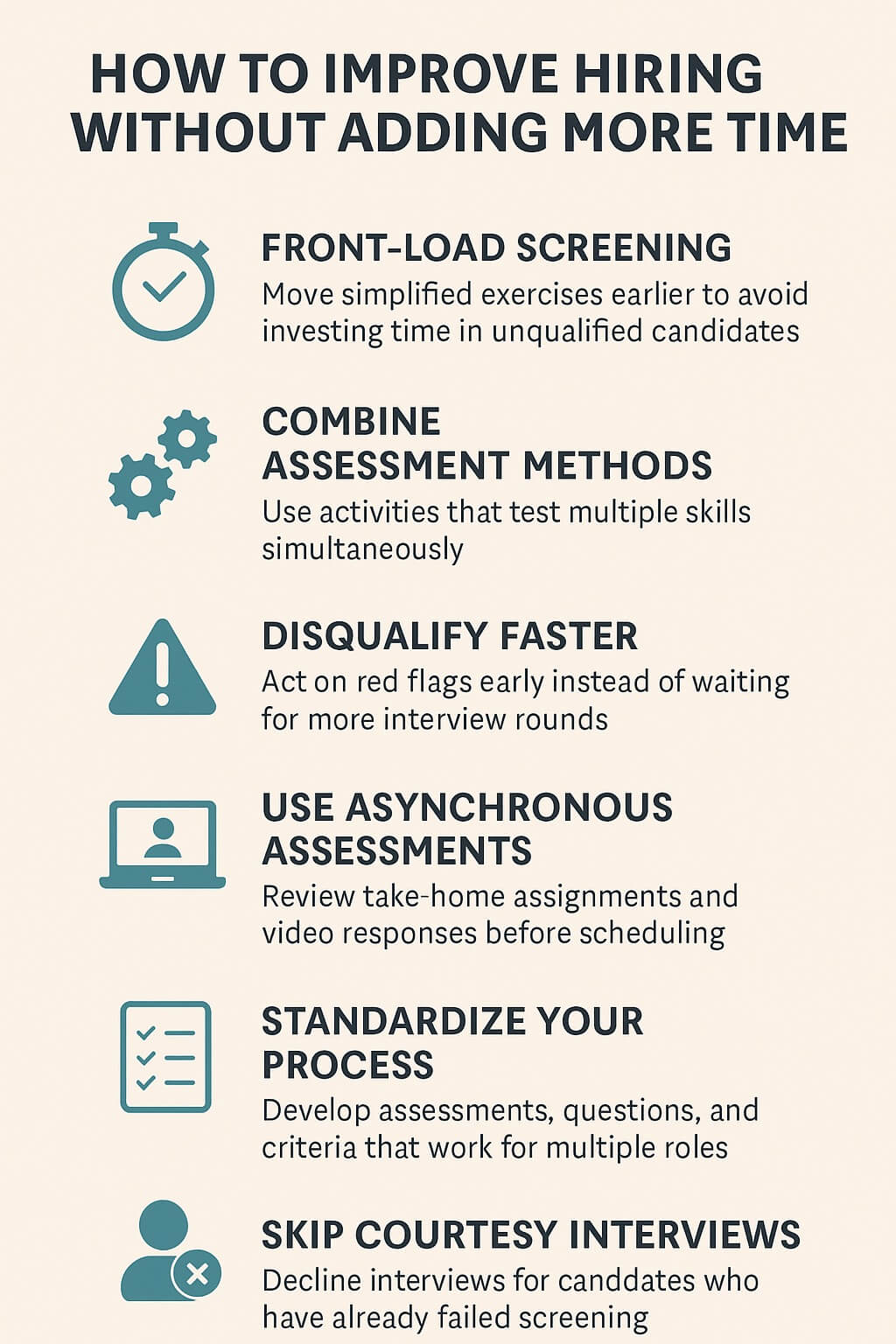

How do I improve my hiring process without adding more time?

Better hiring doesn’t necessarily mean longer processes. Strategic changes to what you do and when you do it can improve outcomes while potentially reducing time invested.

Front-load the screening that’s currently happening in later rounds. If candidates typically fail your technical assessment, move a simplified version earlier so you’re not investing interview time in people who won’t pass anyway. A fifteen-minute screening exercise before first-round interviews saves hours of time spent on candidates who won’t work out.

Combine assessment methods so you’re testing multiple things at once. A practical exercise that requires candidates to explain their thinking tests both technical ability and communication skills simultaneously. Group exercises reveal teamwork, pressure response, and interpersonal skills in one activity. Getting multiple data points from one interaction is more efficient than separate interviews for each trait.

Be willing to disqualify candidates faster based on red flags. If someone shows poor communication or concerning attitudes in early interactions, trust that signal rather than thinking they’ll be different if you give them more chances. Hiring managers often ignore early warning signs and waste time on additional interviews hoping the red flags were flukes. They usually aren’t.

Use asynchronous assessments that don’t require scheduling. Give candidates assignments they complete on their own time, then review the results before deciding who to interview. This screens for actual ability while respecting everyone’s schedules. Video responses to questions, writing samples, or take-home exercises can eliminate candidates who look good on paper but lack real skills.

Standardize your process so you’re not reinventing it for every role. Develop good assessment exercises, effective interview questions, and clear evaluation criteria that you can adapt across positions. The time you invest in building a solid process pays off by making each individual hiring decision faster and more accurate.

Stop doing courtesy interviews for candidates who’ve already failed your screening criteria. It’s kind to give feedback, but you don’t need to interview someone in person if their application materials or screening results clearly show they’re not qualified. Protecting your team’s time is also important.

What’s the single most important change I can make?

If you could only change one thing about your hiring process, shift from evaluating what candidates have done to evaluating how they think and respond to new situations. Past experience matters, but someone’s approach to unfamiliar challenges tells you more about future performance than their list of previous projects.

Create scenarios or exercises that candidates haven’t seen before and can’t rehearse. Give them incomplete information and watch how they work through it. Present them with a problem that doesn’t have one right answer and see how they weigh different options. Ask them to explain something they know well to someone who doesn’t understand it. These situations reveal authentic capability rather than practiced performance.

The candidates who thrive in unfamiliar territory during interviews are the same ones who’ll handle new challenges well on the job. Those who rely heavily on preparation and rehearsal will struggle every time the job throws them something unexpected, which it inevitably will. You want people who can think, not just people who can prepare.

This doesn’t mean technical skills don’t matter or that you should hire people without relevant experience. It means that once someone meets your baseline requirements, their ability to learn, adapt, and solve new problems matters more than whether they’ve done this exact job before. The future of work is unpredictable, and rigid expertise in yesterday’s methods matters less than flexible intelligence applied to tomorrow’s challenges.

Making this shift requires you to trust your evaluation of how people think rather than relying on credentials and experience lists that feel more objective. It’s uncomfortable at first because you’re measuring something less tangible, but the improved quality of hires makes it worthwhile. The perfect resume candidate who freezes with an unexpected question has shown you exactly what they’ll be like on the job. Believe them.

One thought on “How to Stop Hiring People Who Look Perfect on Paper But Fail on the Job”